Lab 3: Operational Amplifiers and Marine Sensors

Team Size: 2

Prelab Help Sheet: html

Writing Assignment: html

1 Introduction

In this lab you will use operational amplifiers to build a turbidity meter, a sensor that measures the relative clarity of water. Turbidity is an interesting and useful measurement in oceanography, so this turbidity meter could be a stepping stone towards your final project. Further, the op-amp techniques that you use to construct this turbidity meter will be useful in any final project you select; the ability to buffer, shift and scale Voltages and currents is essential to many instruments.

After successful completion of this lab, you will be able to

This lab will be carried out as sub-teams of two. Policies for sub-teams are discussed in lab 2.

This lab asks you to prepare solutions and handle chemicals. Though we aren’t working with anything hazardous (or which can’t be flushed down the drain), be sure to observe good chemical hygiene practices and use gloves and goggles when handling chemicals or sensitive equipment. Always use gloves when handling any glassware that will go into the turbidity meter.

There are a few resources used in this lab that must be shared. Please respect others and don’t abuse these resources. All the teams in lab are going to have to share a single turbidity meter and beaker of mystery solution. There will be three digital scales available.

2 Op-Amp Familiarity and Offset Amplifier

In this section, we are going to demonstrate an op-amp failing to work properly, and then we will correct that failure by modifying the op-amp circuit. The modified circuit will be an offset amplifier, which is one of the most common circuits in the final project.

If you would like efficient help in debugging your circuits, it’s important to have a neat and organized breadboard. Here are some tips for keeping your breadboard neat and organized:

- Use color-coded wires to indicate different types of connections. Red wires are typically used for positive power supply connections, black wires are typically used for ground connections, and other colors are typically used for signal and jumping connections.

- Use short wires whenever possible to reduce clutter and make it easier to trace connections. Wires should not cross each other unnecessarily, and they should not have unnecessary bends or loops.

Do the following:

- Use an MCP601 to build a single-rail, non-inverting amplifier with a gain of two. Pay attention to the maximum allowed supply Voltage. Use a 5 V supply Voltage.

- Apply a 100 mV amplitude sine wave with a 1 V offset to the amplifier input and observe the output. This output should match simple theoretical calculations well.

- Apply a 100 mV amplitude sine wave with a 0 V offset to the amplifier input and observe the output. This output should have severe non-idealities related to the amplifier behavior. Identify the non-idealities, and explain why they are present in the output.

- Design, build and test an offset amplifier that can take a 100mV amplitude sine wave with 0 V offset and produce an output with none of the non-idealities in step 3. Use a 5 V supply Voltage and aim for a gain of negative two (an inverting gain) and an appropriate offset.

We are using the MCP601, MCP6002 and MCP6004 in this lab because they are single rail op-amps that are easy to power from a battery. That makes them particularly useful in the final project. You used a few dual rail op-amps in lab 2, and some final projects might demand dual rail op-amps for exacting measurements. For instance, extra credit 1 demands a TL081 for good reason. Talk to an instructor if you want to learn more about the difference between op-amps, which largely have to do with input impedances, output voltage ranges, and some properties that can affect uncertainty.

3 555 Timer LED Driver

Turbidity is a measurement that depends on illuminating a water sample, then measuring the ratio of transmitted and 90° scattered light. We are going to use an infrared light-emitting diode (IR LED) called the IR1503 to illuminate our sample, and we are going to blink it on and off using a circuit called a 555 timer. Because IR radiation is invisible to the human eye, we need a sensor to tell if our system is working, and the OP950 IR photodiode serves that job well.

- Build an astable 555 timer oscillator that has a frequency between 500 Hz and 1 kHz and an output waveform duty cycle of approximately 60%. If you use reference designs from the datasheet, omit RL from any circuit you build.

- Verify that your oscillator is working by measuring the oscillator output Voltage and the capacitor Voltage.

- Attach a series combination of a resistor and an IR1503 the output of the 555 timer. Select the resistor value and diode orientation such that you will drive 20-40 mA through the diode when the output is high. Selecting this resistor will require approximating the diode’s forward voltage (VF) at your desired current level, and information in the datasheet can help you figure out an appropriate VF.

- Measure the Voltage across the resistor in the resistor-IR1503 combination while the 555 timer is operating. Check that this Voltage waveform implies that the correct current waveform is passing through the IR1503.

- Build the switching time test circuit in the OP950 datasheet and use it to check that IR light is coming out of your IR1503. It’s easy to get the OP950 backwards or to pick an unsuitable resistor value, so play around a bit with flipping your OP950 polarity or trying a few different VR and RL values.

LEDs, like all diodes, have an exponential relationship between the voltage applied across them and the current that passes through them. That means applying voltage carelessly can easily blow them up. We prevent such explosions by installing a resistor in series with our IR1503 when we use them. Note that you don’t have to calculate the exponential behavior of the diode because graphs and tables in the datasheet have all the information you need.

The OP950 has similar behavior, so hook it up in series with resistors when you’re testing it on its own. However, we usually use OP950s in transimpedance amplifiers (see Section 4), which protects them from careless overvoltage conditions.

This reference provides background information on LEDs and photodiodes.

4 Transimpedance Amplifiers

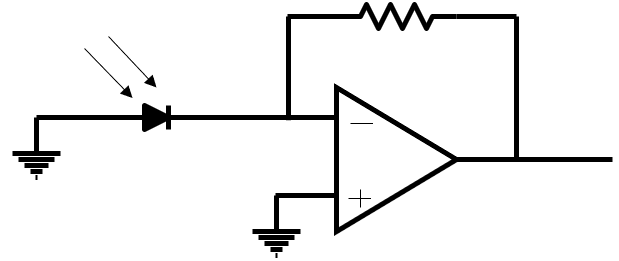

We will need to measure the amount of light that passes through a solution (either by transmission or 90° scattering) in our turbidity meter. The current through a photodiode is linear in irradiance (see the Light Current vs. Irradiance figure in the OP950 datasheet), so measuring the current passing through a photodiode is equivalent to making a linear measure of incident optical power. That’s great for us, but we don’t know how to measure currents yet. Fortunately, op-amps can help with this, but only if we build a new kind of circuit, called a transmipedance amplifier, which is pictured in Figure 1.

- Analyze the transimpedance amplifier circuit to determine a formula that relates the diode current, ID, the feedback resistance, RF, and the output voltage, VOUT. Note that the diode acts like a current source pointing away from the op-amp when the photodiode is illuminated.

- Build a transimpedance amplifier using the MCP6004 and an OP950. The MCP6004 contains four op-amps, which is useful for space-saving. Configure unused op-amps on your MCP6004 as unity gain buffers with their inputs and outputs grounded.

- Use your LED light source from Section 3 to test the transimpedance amplifier. If you are seeing no signal, try flipping your OP950 around. Adjust the feedback resistor so you are seeing a large output signal.

- Build and test a second copy of this op-amp circuit for use in your turbidity meter.

Note: Transimpedance amplifiers can be designed in many ways. The design we are recommending that you use is not the highest-speed design. High-speed designs will reverse bias the diode to reduce its junction capacitance (a type of parasitic capacitance found in all diodes) and add a capacitor in parallel with the feedback resistor to filter out noise. However, applying the reverse bias makes current flow the other direction, which would require that the op-amp be dual rail or have an offset to ensure correct operation. This design is the simplest for a single-rail system, and it doesn’t lose performance when measuring large, slow signals like ours.

5 Turbidity Measurements

Now it is time to assemble and use the turbidity meter. You will prepare solutions of known turbidity using the TU-2016 calibrated laboratory turbidity meter, illuminate them with the LED from Section 3, then measure the transmitted and 90° scattered light using the transimpedance amplifiers from Section 4. Arranging all of these elements – the sample cuvette holding your solutions, the LEDs and the photodiodes – requires a little bit of mechanical finesse, so we provide a 3D printed fixture (instructions, Solidworks for base, Solidworks for cover) for holding the cuvette, LED and photodiodes.

You can Damage the Turbidity Meter

- DO NOT EVER OPEN THE CALIBRATION STANDARDS

- Never touch the glass of the turbidity testing containers with your bare fingers. Handling them with clean gloves is OK.

- Be sure to read the TU-2016 instruction manual to familiarize yourself with the operation of the meter before using it.

- Prepare a set of solutions of different turbidities using milk and water. Use cuvettes to hold your solutions. You should not need to fill the cuvettes more than 1/2 full. Eyedroppers or beakers may help you to add more precise volumes of milk to your solution.

- Check the turbidities of your solutions using the TU-2016.

- Assemble your turbidity measurement setup. Note that you can connect your circuits to the measurement fixture in two ways: (1) solder long wires to the OP950s and IR1503 then connect those to a breadboard, or (2) place your measurement fixture directly on top of the breadboard and put the diode feet directly into breadboard rows.

- Measure your solutions with your own turbidity measurement setup and record the peak-peak Voltages of your 90° and transmission transimpedance amplifier outputs.

- Plot the ratio of the 90° Vpp to the transmission Vpp against the calibrated turbidity of your solutions.

- Add a line of best fit and appropriate uncertainty measurements.

- Examine the effect of ambient light on your measurements by shadowing your experimental setup while watching a transimpedance amplifier Voltage. Use your observation to justify why we switch our LED on and off with the 555 timer and why we care about peak-peak voltages instead of absolute voltages.

Turbidity is an optical measurement that is related to the total undissolved solids in the water. Turbidity is an important environmental monitor since undissolved solids can be indicative of eroded runoff, disturbance of the sea floor or other sources of particles.

Modern electronic measurements of turbidity are measured by shining light through a sample and measuring transmission — how much light passes directly through — and 90° scattering — how much light bounces off the particles to a sensor located at 90° relative to the light source.

Devices which measure only 90° scattering are called nephelometers, and devices which measure the ratio of the 90° signal to the transmitted signal are called turbidity meters or turbidimeters. The relative effectiveness of the two devices depends on exactly how many solids are in the water.

This link has some additional information about turbidity, including a picture of some suspensions of different turbidity for visual reference.